|

|

© copyright 2003 Michael P.

Hamilton, Ph.D.

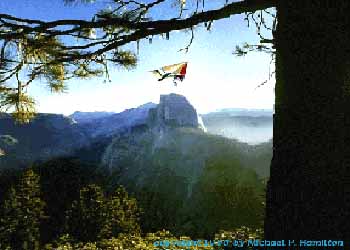

To soar like the condors

December 9, 1996:

With my Powerbook nestled safely on my lap, I peered from

my Black Mountain perch and watched the sky for evidence of the approaching

storm front. On the display of the computer was the latest enhanced

satellite image of California (courtesy of the NOAA web site), graphically

portraying the varied patterns of rain-bearing clouds pulled along by

the approaching wave of low pressure. The storm was already bombarding

the Central California coastline with warm pacific rain, and giving

every indication that it was heading our way. Concentrating on the details

of the image and my "real-time" view of the northwest sky,

my attention was momentarily distracted by an unusual sound. Looking

up I was surprised by a pair of Red-tailed Hawks who were using the

strong ridge lift generated by the approaching storm to hover within

20 feet of my head. Wind pushed over and under their smooth wings provided

them all the lift they needed to remain motionless and nearly silent

as they observed me, perhaps satisfying their curiosity or apprehension

that I was not going to harm them. The nearly inaudible vibration of

their wing feathers was all that gave away their presence to me.

Watching the hawks soar and hover, my mind was drawn to

a scene from my memories. It was nighttime during the summer of 1975,

and a small group of friends and I were clandestinely working our way

up a back country trail in Yosemite National Park towards the summit

of El Capitan, one of the most famous rock faces in all of North America.

El Capitan is viewed by thousands of people a year, while an elite minority

of enthusiasts chooses to climb the 3,593 foot vertical face using only

ropes, chalks, and their wits. We were determined to be the first people

to ever throw ourselves off the top -- in hang gliders!

When we were seasonal wilderness patrolmen with the State

Park in 1973, Bob Smead and I ran into a couple of guys who had hiked

from Humber Park to the top of San Jacinto Peak with hang gliders, intending

to jump off the summit. Then there were no laws against hang gliding

in the wilderness, why recreational hang gliders had only been invented

shortly before that time, and few people were thought to be crazy enough

to consider jumping from an 11,000 foot mountain. Bob and I didn't know

what to do with these guys, they were clearly exhausted from their efforts

at carrying two 80 pound gliders so many miles. So we helped them take

their load to Round Valley, and suggested that perhaps the escarpment

near Hidden Lake would be a good spot to launch. The pilot seemed happy

about this alternative, and gave me one of his business cards with the

invitation that Bob and I contact his hang gliding business so he could

give us flying lessons.

Their flight was successful (although they ended up flying

off of the water tower next to the Tramway), and after a summer of free

lessons, I wrote them a check for a brand new Wills Wing Hang Glider.

So began a ten year adventure of flying off local mountain peaks, soaring

with hawks along the sea cliffs of San Diego, and jumping from several

of the Yosemite Park "Big Walls" including Glacier Point.

I found myself doing things that I would never have considered possible

had I not been learning from the best pilots in the world. The hike

up El Capitan was arduous to say the least, but when we woke up in the

morning to a clear sky and calm air, our hearts began to soar like the

condors we emulated while we assembled our gliders and prepared for

the flight. Gradually the air began to rise from the Valley floor and

the first of our group of five pilots took a half-dozen or so running

steps and launched themselves into 4,000 feet of vertical air space.

The butterflies I felt in my stomach seemed to help me gain an extra

amount of lift as I earned a view of Yosemite Valley that only four

others in the entire world had ever seen, suspended beneath the rugged

aluminum and dacron of my condor-shaped hang glider.

previous journal entries

|