© copyright 2003 Michael P. Hamilton, Ph.D.

Moving Beyond Place

February 27, 1998:

Some of you have already been exploring the new James Reserve web site, but the advent of online interactivity means a lot more than a convenient way to find out general information about this Reserve. For more time than I like to think, several of my colleagues and I have held firm to the vision that an ecological reserve is much more than a place to bring your field classes to study ecology, or to send your graduate students to learn the honorable activity of field research. The notion of a ecosystem library merely scratches the metaphoric surface of all the things that an NRS reserve has become. Thanks to the technological wizardry of the Internet we can now add to this list "virtual reserve," the implications of that being the cause of many nights of lost sleep!

Perhaps the last thing some of our NRS founding mothers and fathers want to think about is a reserve without a landscape...artificial nature...field science without the field...why, that is ecological blasphemy!!! But wait, before erecting the banner of eco-luddite, lets explore for a moment what the benefits of a virtual reserve might be to our NRS. The ecosystem library of the NRS consists of 33 sites that are spread all over this great and diverse state of California. To access the entire "library," even for a single day per reserve, would entails a minimum of one month of travel (allowing an average of 4 hours of travel time between reserves), and following a circuitous route of nearly 1,500 miles while consuming over 100 gallons of fossil fuel. If you wanted to observe an example of every dominant plant community and wildlife habitat that exists on each reserve, you would need to triple the number of days spent exploring those landscapes. After three months of examining the ground, additional time will be needed to sift through countless reprint boxes and file cabinets to peruse all of the scientific studies, reports, master's theses, doctoral dissertations, publications, books, databases, photomonitoring studies, and amassed knowledge located in the offices, laboratories and libraries at each reserve. Don't forget that every UC campus (except UCSF) also has a connection to a cluster of reserves, so include in your survey a visit to each of UC campus NRS office for several days of study. By now it is apparent that our NRS ecosystem library has taken on a scale that goes beyond the complexity and depth of a traditional library holding...and as any Ph.D. candidate will tell you, it is very easy to spend years learning about all of the jewels that exist within any of our UC libraries.

Would anyone take on such a survey of the NRS ecosystem library? Not yet -- the time and logistics of such a task precludes the on-the-ground longitudinal approach needed to compare ecology and environmental diversity across the entire Natural Reserve System. But what if much of that knowledge and information were available through the Internet? What if identical experiments could be established at each of the 33 NRS reserves, and data collected effortlessly by a software data mining agent deployed over the Internet? The ecological ramifications of global scale phenomena such as El Nino could be tracked in real time and at multiple scales...exploring the physical environmental changes of extreme rainfall events as they impinge upon hydrology, soil processes, vegetation dynamics, invertebrate populations, animal migration, food chains, and an infinite web of ecological interconnections...all of a sudden becomes logistically viable and intellectually interesting. Historical information could be consulted without cost to the scientist, and time series data, be it environmental measurements, photographic monitoring, or census records, become useful by many more people than would ordinarily visit or work at a particular reserve.

The virtual reserve adds real value to the physical reserve by expanding the usefulness of information without forcing our directors and stewards into the difficult decision of determining how much MORE use is too much. Overuse by researchers, classes, and the public threatens the intrinsic ecological and environmental values which justified the establishment of the reserve in the first place. The virtual reserve may provide an alternative methodology for scientists who normally pay regular visits to a reserve to collect data from experiments, by allowing them to remotely access their data loggers, and to search reserve-based library records or databases from their own office. I admit that the majority of field research and teaching activities will, by necessity, continue to require the intimacy of real visits to our reserves... that is a legacy that could never be replaced. But for those reserves that are at their carrying capacity; or for new research that asks questions requiring transects across large geographic areas within short sampling intervals; or for distance learning via the California Virtual University -- a virtual reserve might satisfy many of these new and unique needs without overloading a particular reserve's user carrying capacity.

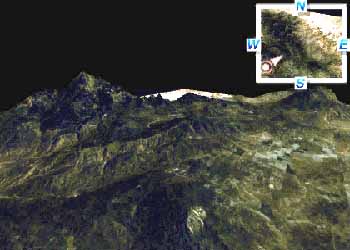

At the James Reserve we are now exploring the concept of virtual reserve, and even at this very preliminary stage of implementation, an eager group of on-line users are emerging. In the three months that our web site has been in place, nearly 2,000 unique visitors have logged in, and one fourth of those have either down-loaded data, or made requests for information which has not yet been posted on our web site. Our web-based reservation system is making it easy for users to find an available time to visit, then determine what permits and user applications are needed, and finally submit their requests without the cost of telephone calls or the delay of the US Mail. We are in the process of digitizing hundreds of thousands of pieces of information, including a 50 year weather database, 18 years of bird banding records, 20,000 photographs (some taken more than 75 years ago), 20 billion bytes of remote sensing data ranging from 30 meter resolution multi-spectral satellite scenes to 5 centimeter resolution aerial video surveys, and an interactive geographic information system with thousands of site-specific features delineated across the entire San Jacinto Mountains.

In late 1998 we intend to install several radio-linked, remotely operated, multi-spectral video cameras situated within the James Reserve so that a user can look across a 360 degree panoramic view, and telescopically enlarge the live scene via controls on their web page. These cameras will have sufficient resolution to view flowering plants, or watch particular wildlife. We will be placing tiny infrared cameras into several bird boxes and bat houses in order to non-invasively document the growth and development of nestling birds, and monitor the daytime activities of roosting bats. Imagine bird feeders that can be remotely opened or closed, that can be viewed via web cameras, augmented with pattern recognition java script software to automatically count and identify bird species that stop for food -- perhaps even identifying marked individuals. Down the road we plan to explore the use of tele-robotic pit traps which capture, mark, and release small organisms after they are identified...and mobile autonomous "data-droids" that mimic rocks and logs to make "stealthy" close range observations of animal activities such as pollinator visitation, territorial interactions, or foraging behaviors. The data collected by these droids will be transmitted to small stationary data loggers that are directly accessed from the Internet via a solar powered radio linked ethernet. Did I mention time-lapse photography? Stereoscopic panorama landscape cameras can collect plant growth measurements of thousands of trees, shrubs and herbs using volumetric image processing and change detection algorithms...and these phenological trends can be statistically compared to environmental measurements from temperature, precipitation and solar radiation sensors. The list of possibilities is rather mind expanding if you ask me!

With the next millennium rapidly approaching, and global environmental change an accelerating reality, increased expectations for identifying and solving ecological problems compel me to consider how we can enhance the current paradigm of our reserves as places for science by exploring new relationships between society and nature...a relationship that may someday become an integral component for a new global ecological consciousness.