Fire-Scope

Sitting safely on top of the giant boulders near Black Mountain, I rotated the trackball of my laptop computer to electronically move an imaginary mountain range. Suddenly the outline of computer generated peaks, ridge lines and valleys began to resemble the very same panorama I was experiencing from my mountain top lookout, with a single significant exception, the real landscape I was viewing was on fire!

Earlier today I packed up my computers and family photographs and locked the doors of my home in Idyllwild to head for the James Reserve. I know I was supposed to leave the Hill, most of you did, but I had much work to do to prepare the Reserve facilities for the chance that the Bee fire might be heading that way. Upon arrival the first order of business was to set up the computers and install the Forest Stewardship Database. Years in the making, this computerized geographic library of the entire San Jacinto Mountains contained detailed maps of natural vegetation, fuel types, topography, wind movements, and land uses. Best of all, it gives us the means to understand the spread of fire under different weather conditions.

After installing files into my portable Powerbook computer, and entering the most recent Forest Service fire perimeter data that Pat Boss had provided on my way out of town, I hiked up to the highest point near the Reserve where I could gain a vantage point of the fire. With binoculars I could clearly watch ground level firefighters perched along the slopes of Indian Mountain. Flames were visible to me along the northwest ridge line of Indian Mountain, and one air tanker after another was bombarding the wild fire with the bright pink fire retardant. The pilots were incredible in their mastery of the art of dropping their load of retardant precisely upon the vegetation that was just beginning to burn. From where I was sitting I could estimate that the line of fire was less than two miles away and burning in this direction!

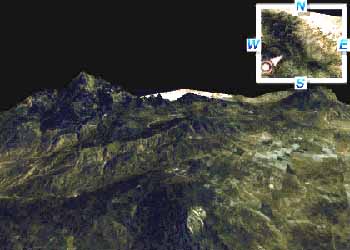

Activating the Forest Stewardship Database software, I queried the topographic map index for the portion containing Indian Mountain. Viewable with a three dimensional perspective, I interactively twisted and zoomed into the colorful shaded relief map until the computer display approximated the same view I could see through my binoculars. Over the years my students and I have constructed dozens of computerized maps after carefully studying satellite and aerial images, maps that can be precisely superimposed upon the realistic 3-D model. I called up a map of historic fire boundaries which superimposed itself onto the digital view of Indian Mountain. The fire line that I now watched burning in the northward direction was attempting to ignite vegetation that had last burned in the 1974 Soboba Fire.

My "fire-scope" showed that the flames were moving towards a moist drainage, and it would have to burn against the prevailing wind to accelerate. Another digital map portraying overall fire hazard severity suggested that the fire would dramatically diminish in rate of spread and intensity as it attempts to consume the vegetation between there and here.

The real danger, of course, was with the south and west moving flanks of the fire. It was apparent that the fire was burning rapidly into the North Fork drainage and could leap across the canyon to make a run up towards Logan Creek and the northwest side of Pine Cove. By merging fire hazard maps and property boundaries, I identified numerous critical points where the fire line could threaten homes.

Knowledge is said to be power, but what is the power of knowing what might happen, yet not be able to do a thing about it. Fortunately the fate of our mountain communities was in the very capable hands of expert fire fighters. That night, the fire that was threatening the James Reserve was put out, and the remaining fires moved closer and closer to Pine Cove and Idyllwild Arts.

What happened next, well, that is already old news!