On the Trail to the Electronic Museum

Climbing Black Mountain from the James Reserve is normally a sweaty, scratchy, deer fly in your face kind of experience. Today would prove to be no different, particularly for my companion, a desk-bound video engineer who admitted he smoked too much and was entirely out of shape, even for a flatlander. In fact, it would probably be worse as we were carrying nearly 100 pounds of video recording equipment to locations that would require some rock climbing. I just wish Jim had warned me that he was afraid of heights.

During our first two years at the James Reserve my wife and I kept busy renovating Harry James's old cabin (our new home), installing solar photo-voltaic panels, plugging holes in the log walls, entertaining visiting scientists, raising a new baby and keeping warm. I also spent a lot of time writing a plan for an electronic catalog of the flora and fauna of the Reserve, based upon the research from the Virtual Aspen Project. My proposal was completed after about a year of work, and I had a great deal of naive confidence that my idea of an "Electronic Museum" would win over potential grant agencies by its sheer level of innovation...was I wrong! After dozens of polite "no thank you" rejection letters, there was finally a brave foundation willing to give me a seed grant to build a less elaborate demonstration of the concept, and use it persuade another agency to give me my major grant.

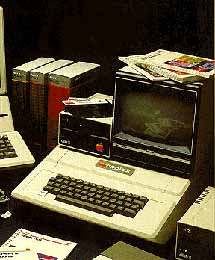

The mini-grant let me buy a brand new Apple II computer, a laserdisc player, and software. Later, I constructed a "black box" that would allow the computer to directly control the laserdisc player. I had just enough grant money remaining to rent for a single day a broadcast quality video camera and portable VCR, plus a technician to operate the equipment. My script required we videotape approximately fifty locations between Lake Fulmor and Black Mountain, in the format of a spiraling panorama. Imagine looking down at your feet through the viewfinder and slowly panning all the way around until you reached the same point you started. Tilt the camera up a few degrees, and repeat the pan. Continue this process until eventually the last panorama is one of pointing nearly straight up at the sky. The videotape records a "view map" of that location which, when controlled by computer and laserdisc, can be used to simulate standing and looking in any direction you choose.

We continued to travel around the Reserve, videotaping panoramas at all fifty locations, and collecting hundreds of close-up shots of wildflowers, lady bugs, woodpeckers, lizards and anything else that caught my young naturalist eye! Working our way up Hall Canyon, the locations became increasingly steeper and more exposed, thus affording overviews of the same forests we had been videotaping earlier in the day. My assistant was very quiet during these highly precarious shots, and I thought he was simply exhausted from lack of stamina. As I scrambled up the last few feet on a 50 foot cliff face, and pulled out a rope to help hoist the equipment, I noticed that Jim's face was nearly white and dripping with sweat. He was shaking and was barely able to tell me that he had acrophobia and felt as if he was going to die. Once I helped him down, I completed the shot myself and we headed back to the main Lodge to recover.

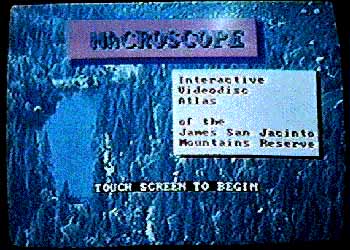

After four months of videotaping maps, photographs and stuffed museum specimens, and later editing the tape so that the entire collection would fit on a 30 minute videocassette, I hand-carried my precious tape to a post-production company in Burbank to be transferred to a single laserdisc. Within a month of indexing the laserdisc and programming the little Apple computer, I had completed a demo of the world's only computer-based interactive multimedia nature walk. Later that month, after a successful demonstration, I received the first of several major grants to develop an Electronic Museum of the San Jacinto Mountains.