So Where Are the Dinosaurs?

The pilot signaled us to come aboard, so we ducked our heads, ran like heck over to the Hughes military helicopter, and climbed inside. I had asked the commander in charge of this flight if we could have the door removed to gain an unobstructed view for shooting video and movie film. He agreed, so our flight would be rather noisy and windy ... and very exciting.

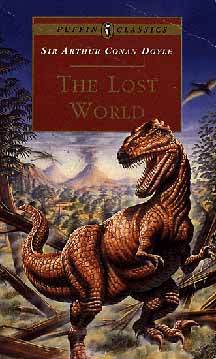

It was time to visit one of the most unusual ecological features in all of Venezuela, the Tepui mesas of the Gran Sabana. When Sir Arthur Conan Doyle wrote his famous novel 'The Lost World' he based his adventure on the exploration of this little known region of Venezuela. The Tepui are a series of ancient mountains formed by the breakup of the continents of South America and Africa millions of years ago. As massive geological forces gradually lifted the land, erosion from ancient rivers, rainfall and wind weathered away the more porous materials, exposing these flat-topped mesas. Geology, topography and climate eventually isolated the tops of the mesas from each other and the connecting landscape below. Arthur Doyle speculated in his fictional story that relict dinosaurs still existed on the tops of these prehistoric Tepui, unable to leave because of the thousand foot cliffs. Today it was our turn to see if the dinosaurs really existed!

The Gran Sabana is an extraordinary place. The tallest waterfall in the world, Angel Falls, plunges nearly 3,000 feet from the summit of Ayuan Tepui. Looking through the viewfinder of my camera I filmed a landscape of flat top mountains, deep green rainforests and large expanses of grasslands and palm trees. There were no roads or other evidence of human habitation in the direction we were travelling. Our destination was to ecologically survey the top of Mount Drivoa, and to collect a rare carnivorous pitcher plant called Heliamphora. After two hours of travel the pilot informed us that we were approaching the summit of the mountain, and to prepare to land. Much of the lower elevations of the mountain was shrouded in a thin white mist, but fortunately for us the upper reaches were in full sunlight. There is nothing quite like a helicopter to get around in normally inaccessible places. I've been spoiled over the years in having the use of helicopters to study wildlife in Alaska, endangered plants in Nevada and Utah, and bighorn sheep in our local Santa Rosa Mountains.

It didn't take us long to unload the helicopter and watch it depart, then set up camp and begin our botanical survey. A well-known Venezuelan botanist, Dr. Otto Huber, was with us on this expedition, and he being quite familiar with the location, we soon discovered the first specimen of Heliamphora minor, the Venezuelan pitcher plant. Pitcher plants are unusual members of a larger group of carnivorous plants that derive their primary nutrition from animals. Their leaves have evolved into ingenious watery traps that attract and ensnare insects. Slippery wax and downward pointing hairs around the rim of each pitcher-like leaf keeps unwitting insects from climbing out until they drown. Specialized enzymes secreted by the cell walls of the pitchers rapidly break down the softer body parts, making food that sustains these plants that ordinarily grow in nutrient-poor acid bogs. Pitcher plants exist in Australia, southeastern and northwestern US, the jungles of southeast Asia, and the rarest here in Venezuela.

These are heady times for young biologists, exploring tropical mountains that fewer than 100 people have ever seen. Before our helicopter returned to take us back to civilization we had collected nearly a hundred specimens of rare and exotic plants, and captured what we hoped to be at least a dozen new species of animals, including bats, frogs and insects. Nowhere in our wanderings did we come across the dinosaurs described in 'The Lost World' ... but you should know we spared no small effort in trying!